This month we introduce two constellations, CORVUS and LEO. Both constellation shapes are easily recognisable in our evening skies. Among these stellar beacons, situated on the Coma – Virgo border, lie prominent galaxies – the ultimate deep sky target.

CORVUS can be found almost directly overhead; it’s squashed box shape defined by bright 3rd magnitude stars.

Although a Northern Hemisphere constellation, LEO is well placed on our northern horizon with it’s characteristic sickle shape hinging on bright Regulus.

GALAXIES

Galaxies are awe-inspiring, the faint fuzzies fuelling our imagination of other galactic neighbourhoods. By studying the galaxies in the universe, we have come to a clearer understanding of galaxy dynamics and the forces which have formed our spiral " the Milky Way ".

Photons that have travelled millions of light years, brought into focus – is one of the pleasures enjoyed only by an astronomer. As a deep sky target, you will be rewarded with a variety of shape and detail, and ultimately test your observing skills. Although challenging, galaxies can be enjoyed starting with the naked eye (Andromeda at 2.2 million light years appears as a fuzzy spot in the sky; the large and small Magellanic Clouds are clearly visible right on our doorstep), binoculars and finderscopes ( M83 and Centaurus A are easily seen in 7x50’s in a dark sky ) and telescopes where one can start to detect detail in a 6" scope. Capturing the faint light on film or CCD is the ultimate in achieving maximum detail.

What can one expect to see when hunting down galaxies ?. The myth that you require a massive light bucket is only partly true, the enjoyment is firstly in finding these collective swarms of stars and dust. A 6" inch telescope will start to show distinctive shape and structure in some of the brighter galaxies, fainter one’s appearing as fuzzy blobs and smudges against the background sky. Larger scopes increase the detail dramatically, with definite spiral arms and dark dust lanes discernible in many of the brighter galaxies. More aperture gives you a license to chase down galaxy clusters, where up to as many as two or more galaxies can fill an eyepiece field ! ( one of our favourites is the IC 4239 group in Centaurus, counting five in this excellent Southern sky example using a 12" f/7 – from a very dark Drakensberg ).

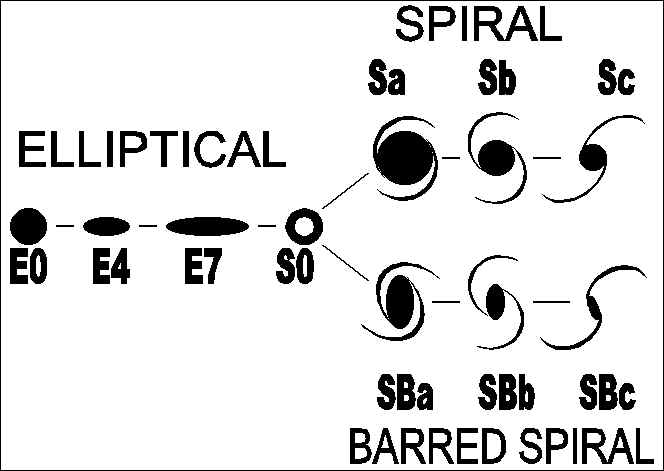

While perusing magazines and essential companions such as Burnham’s Celestial Handbook for possible galaxy targets, it is useful to keep in mind galaxy classification. Not only does this information increase your knowledge of the objects that you are studying, it also gives you an idea of the shape you might expect to see in the eyepiece ( e.g. round or elliptical ). Galaxies come in all shapes and sizes which tell you much about their development and nature. The tuning fork diagram best explains this graphically, and you will soon get used to the terminology

EDWIN HUBBLE devised the tuning fork diagram in 1925 as a simple classification of galaxies. This is still widely used today even though more complex schemes have since been devised.

Hubble’s scheme catagorised galaxies into three main groups, namely elliptical, spiral and barred spiral. Each of these are divided into subtypes according to observable characteristics. The E group are the ellipticals which is followed by a classification number from 0 to 7, depending on the degree of flattening. The S group are the spirals which are divided into two distinct groups, spirals S and barred spirals SB. These are followed by the classification letters a, b or c. In both of these categories the a would classify a galaxy with a dominant nuclear bulge with tightly wound spiral arms progressing to c which would have a lessor central bulge with more open spiral arms.

The less commonly observed irregular galaxies like the large and small Magellanic Clouds, were not included in Hubble’s original diagram.

We would like to take this opportunity to promote a real observing gem. This useful collection of information is an essential deep sky companion. It does not cost an arm or an eyepiece and can fit into the palm of your hand or tucked away in a pocket. It is the "NIGHT SKY" in the "Collins Gem" miniature series of the world at your fingertips ( other titles include survival and the world of dinosaurs – R39.95 Estoril Books ). This is by no means a Mickey Mouse publication, with detailed star charts of all 88 constellations by Will Tirion, the world renowned astrocartographer. This little book can be used as a quick reference at the eyepiece (you might need to know which star is "mu" Orionis to find the planetary nebula Abell 12/ PK198-6.1 which is almost on top of it). The "NIGHT SKY" contains a wealth of information especially useful for the smaller telescope. All the star charts contain descriptions of double and multiple stars, brighter deep sky objects and what you can expect to see, and accompanying articles on various astronomical terminology and paraphernalia. With some knowledge of the constellations, the "NIGHT SKY" is a cost effective alternative set of star charts for the beginner and advanced alike.

THE DEEP SKY STAR HOP

CORVUS the crow is an autumn constellation for the Southern hemisphere. In Greek legend it is connected to Hydra and Crater, and seems to be the beginning of political agenda prevalent of today – " the crow ( CORVUS ) is sent to fetch water in a cup ( CRATER ), but returns with the water snake ( HYDRA ).

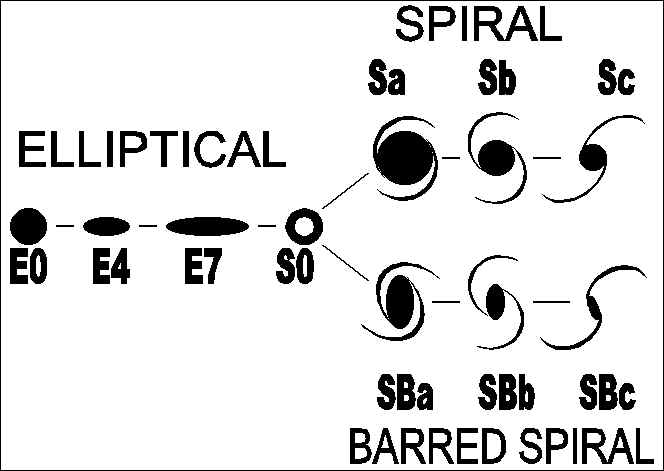

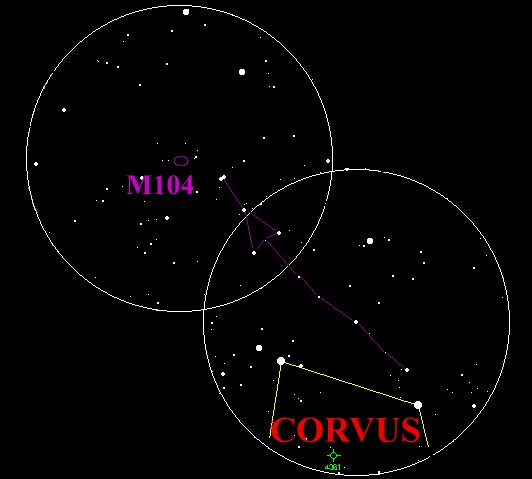

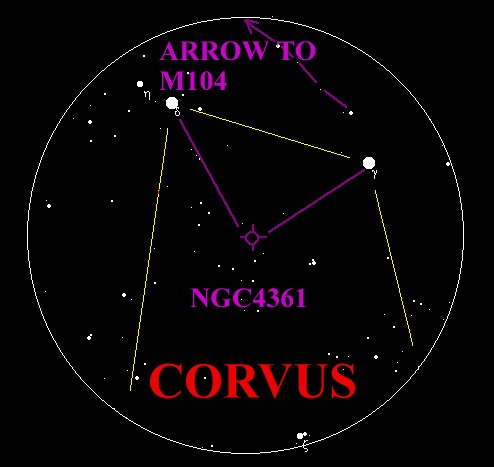

CORVUS can be found by drawing an imaginary line starting at Alpha Crucis (the bottom South-pointing star), go through Gamma Crucis ( the top North-pointing star ), carry on past Centaurus and the next brightest constellation will be CORVUS. One of the bright corners of the box can be seen to have a naked eye companion. The brighter of the two is Delta Corvi, a beautiful easy double for the small telescope. CORVUS is an excellent starting point to find the famous "Sombrero" galaxy M104 by using a cosmic arrow which points the way

Most of you will be familiar with the "M" designation of astronomical nomenclature being awarded to Charles Messier ( 1730-1817), the 18th century French astronomer. His catalogue of nonstellar objects is well known to us amateurs, as many of his catalogued objects (found using his small scope) are the brighter of the deep sky objects that are easy to find. Messier had not set out to produce what became his "CATALOGUE OF NEBULAE AND OF STAR CLUSTERS", but began recording fuzzy objects that did not change position while on his search for comets.

NGC 4594 (the New General Catalogue classification for M104) caused a stir in the astronomical circles in 1921, when it was added to Messiers original 103 objects, and essentially the beginning of a series of modern additions to his catalogue. Controversy still surrounds some of these objects today, his list having grown to 110. Apparently there is evidence for certain objects which Messier knew about, but had not actually observed.

M104 is an excellent example of a galaxy seen nearly edge-on, with many catalogues classifying it as an Sa. The galaxy has a massive nuclear bulge, with an almost stellar central region. An interesting feature of this galaxy which first became visible on long exposure photographic plates, is the more than 2000 globular clusters that surround it’s halo. If you can recall a previous article, globular clusters are very old spherical associations of stars which seem to populate the halos of galaxies – the Milky Way only has about 160. The prominent feature of M104 is the dark lane bisecting this bulge, visible in amateur telescopes.

Starting at Gamma or Delta Corvi, find the head of the arrow as can be seen in the accompanying star chart. If you can find this grouping, it is an easy hop to the galaxy. M104 lies a little to one side in a grouping of six 7th magnitude stars. The galaxy is magnificent and appears as a fairly bright oval in small amateur telescopes. Depending on sky conditions, the dark lane can be visible in a 4 inch scope.

NGC 4361 is a 10th magnitude planetary nebula located near the center of the CORVUS box. This is one of the brighter and larger of planetaries in the sky, and has been seen in telescopes as small as 4 inches. It appears as a large halo of 80 arcseconds surrounding the 13th magnitude central star, the disk a little larger than Jupiter. Due it’s large size it is a challenging object, as one requires higher magnification to increase the contrast of the background sky. Imaging an equilateral triangle with Gamma and Delta Corvi as the base and NGC 4361 will lie at the apex. Try to identify the small triangular grouping as is visible in the accompanying star chart and 7 x 50 finder view, the planetary nebula lies to one side.

LEO has been associated with the Lion since ancient times, and represents the Lion slain by Hercules as the first of his twelve labours. Alpha

Leonis, also known as Regulus, is the brightest star of the constellation. Regulus shares the ecliptic with the planets, and eventually all the solar system objects will pass it by. The easiest way to find LEO is to face the northern horizon. Using bright Rigel in the setting constellation of Orion on the west horizon as your starting point, draw an imaginary line through Procyon in Canis Minor, continuing east in the same direction, will point to Regulus. Regulus is the bright star situated at the top of the sickle or upside down question mark.

LEO contains a number of excellent galaxies and a beautiful pair that is visible in a single low power eyepiece. Gamma is a beautiful double for the small telescope, consisting of two orange – yellow stars of 2nd and 3rd magnitude at a separation of 4.4 arcseconds.

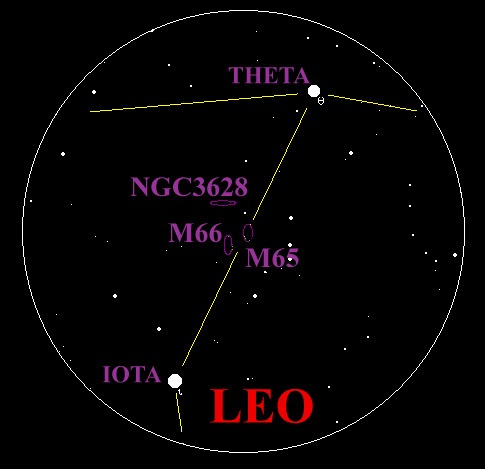

M65 ( Sb ) and M66 ( Sb ) are seen at magnitudes of 9.3 and 9.0 respectively, making them fairly bright galaxies for the small scope. Using either Theta or Iota Leonis as the starting point, imagine a line connecting the two. About midway you will find a distinctive chain of about five stars, the two galaxies can be found just to one side. With your finder on target, pan around using a wider field eyepiece until you find the two slightly elongated grey smudges. If you are viewing with a 6 inch or larger scope, you might bump into a nearby galaxy NGC 3628 ( Sb) at magnitude 9.5, photographically this makes for a stunning grouping.

Objects which were covered in the July '98 article of Southern Sky Star Hopping are also visible again at this time of the year:

| NAME | TYPE | CONST | R.A. | DEC | MAG | SIZE |

| NGC4361 | Planetary | Corvus | (12h24.5m | -18deg 46’) | 10 | 80" |

| M104 | Galaxy | Virgo/Corvus | (12h40.0m | -11deg37’) | 8.3 | 8.9’x4.1’ |

| M65 | Galaxy | Leo | (11h18.9m | +13deg05’) | 9.3 | 10.0’x3.3’ |

| M66 | Galaxy | Leo | (11h20.2m | +12deg59’) | 9.0 | 8.7’x4.4’ |

| NGC 5286 | Globular | Centaurus | (13h46.4m | -51deg 22’) | 7.6 | 9.1’ |

| NGC 5139 | Globular | Centaurus | (13h26.8m | -47deg 29’) | 3.65 | 36.3’ |

| NGC 4755 | Open Clu | Crux | (12h53.6m | -60deg 20’) | 4.2 | 10’ |

| NGC 3918 | Planetary | Centaurus | (11h50.3m | -57deg 11') | 8 | 12" |